- Home

- Harriet Lane

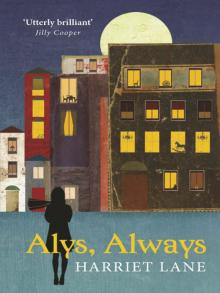

Alys, Always

Alys, Always Read online

For G.S.C.

Alys, Always

HARRIET LANE

Contents

Cover

Dedication

Title Page

Epigraph

Alys, Always

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Copyright

A violet bed is budding near,

Wherein a lark has made her nest:

And good they are, but not the best;

And dear they are, but not so dear.

Christina Rossetti

It’s shortly after six o’clock on a Sunday evening. I’m sure of the time because I’ve just listened to the headlines on the radio.

Sleet spatters the windscreen. I’m driving through low countryside, following the occasional fingerpost toward the A road and London. My headlights rake the drizzle, passing their silver glow over gates and barns and hedgerows, the ‘closed’ signs hung in village shop windows, the blank muffled look of houses cloistered against the winter evening. Very few cars are out. Everyone is at home, watching TV, making supper, doing the last bits of homework before school tomorrow.

I’ve taken the right fork out of Imberly, past the white rectory with the stile. The road opens up briefly between wide exposed fields before it enters the forest. In summer, I always like this part of the drive: the sudden, almost aquatic chill of the green tunnel, the sense of shade and stillness. It makes me think of Milton’s water nymph, combing her hair beneath the glassy cool translucent wave. But at this time of year, at this time of day, it’s just another sort of darkness. Tree trunks flash by monotonously.

The road slides a little under my tyres so I cut my speed right back, glancing down to check on the instrument panel, the bright red and green and gold dials that tell me everything’s fine; and then I look back up and I see it, just for a second, caught in the moving cone of light.

It’s nothing, but it’s something. A shape through the trees, a sort of strange illumination up ahead on the left, a little way off the road.

I understand immediately that it’s not right. It’s pure instinct: like the certainty that someone, somewhere out of immediate eyeshot, is watching you.

The impulse is so strong that before I’ve even really felt a prickle of anxiety, I’ve braked. I run the car into the muddy rutted margin of the road, up against a verge, trying to angle the headlights in the appropriate direction. Opening the car door, I pause and lean back in to switch off the radio. The music stops. All I can hear is the wind soughing in the trees, the irregular drip of water on to the bonnet, the steady metronome of the hazard flashers. I shut the door behind me and start to walk, quite quickly, along the track of my headlights, through the damp snag of undergrowth, into the wood. My shadow dances up ahead through the trees, growing bigger, wilder, with every step. My breath blooms in front of me, a hot white cloud. I’m not really thinking of anything at this moment. I’m not even really scared.

It’s a car, a big dark car, and it’s on its side, at an angle, as if it is nudging its way into the cold earth, burrowing into it. The funny shape I saw from the road was the light from its one working headlamp projecting over a rearing wall of brown bracken and broken saplings. In the next few seconds, as I come close to the car, I notice various things: the gloss of the paintwork bubbled with raindrops, the pale leather interior, the fact that the windscreen hasn’t fallen out but is so fractured that it has misted over, become opaque. Am I thinking about the person, or people, inside? At this moment, I’m not sure I am. The spectacle is so alien and so compelling that there’s not really any space to think about anything else.

And then I hear a voice, coming from within the car. It’s someone talking, quite a low, conversational tone. A sort of muttering. I can’t hear what is being said, but I know it’s a woman.

‘Hey – are you all right?’ I call, moving around the car, passing from the glare of the headlight into blackness, trying to find her. ‘Are you OK?’ I bend to look down into windows, but the dark is too thick for me to see in. As well as her voice – which murmurs and pauses and then starts again, without acknowledging my question – I can hear the engine ticking down, as if it’s relaxing. For a moment I wonder whether the car is about to burst into flames, as happens in films, but I can’t smell any petrol. God, of course: I have to call for an ambulance, the police.

I pat my pockets in a panic, find my mobile and make the call, stabbing at the buttons so clumsily that I have to redial. The operator’s answer comes as an overwhelming, almost physical relief. I give her my name and telephone number and then, as she leads me through the protocol of questions, I tell her everything I know, trying hard to sound calm and steady, a useful person in a crisis. ‘There’s been an accident. One car. It looks like it came off the road and turned over. There’s a woman in there, she’s conscious; there might be other people, I don’t know, I can’t see inside. Wistle-borough Wood, just outside Imberly, about half a mile past the Forestry Commission sign – up on the left, you’ll see my car on the road, it’s a red Fiat.’

She tells me help is on its way and I hang up. There’s quiet again: the trees creaking, the wind, the engine cooling. I crouch down. Now my eyes have adjusted, I can just make out an arm, thrown up against the side window, but the light is so dim that I can’t see any texture on the sleeve. Then she starts to speak to me, as if she has woken up, processed my presence.

‘Are you there?’ she’s asking. She sounds quite different now. There’s fear in her voice. ‘I don’t want to be on my own. Who’s there? Don’t go.’ And I kneel down hurriedly, and I say, ‘Yes. I’m here.’

‘I thought so,’ she says. ‘You won’t leave me, will you?’

‘No,’ I say. ‘I won’t leave you. There’s an ambulance on its way. Just stay calm. Try not to move.’

‘You’re very kind,’ she says. It’s the sort of expensive, cultured voice that goes with the Audi, and I know – hearing that particular voice making that particular remark – that it’s a comment she makes dozens of times a day, without even thinking about it, when people have shown her courtesy or deference at the farm shop or the butcher’s.

‘I’ve got myself into a bit of a mess,’ she says, trying to laugh. The arm moves, fractionally, as if she is testing it out, and then lies still again. ‘My husband is going to be so cross. He had the car cleaned on Friday.’

‘I’m sure he’ll understand,’ I say. ‘He’ll just want to know you’re OK. Are you hurt?’

‘I don’t really know. I don’t think so. I think I knocked my head, and I don’t think my legs are too good,’ she says. ‘It’s a nuisance. I suppose I was going too fast, and I must have hit some ice … I thought I saw a fox on the road. Oh, well.’

We wait in silence for a moment. My thighs are starting to ache and the knees of my jeans, pressed into damp bracken, are stiff with cold and water. I adjust my position and wonder how long it will take the ambulance to get here from Fulbury Norton. Ten minutes? Twenty? She doesn’t sound terribly hurt. I know it’s not a good idea to interfere in a car accident, but maybe I should try to help her out somehow. But then again, if she has a broken leg … and anyway, I have no way of opening the car door, which is crumpled and pleated between us, like a piece of cardboard.

I cup my hands and blow on them. I wonder how cold she is.

‘What’s your name?’ she asks.

‘Frances,’ I say. ‘What’s yours?’

‘Alice,’ she says. I might be imagining it, but I think her voice is sounding a little fainter. Then she asks, ‘Do you live around here?’

‘Not any more. I live in London. I’ve been visiting my parents. They live about twenty minutes away – near Frynborough.’

‘Lovely part of the world. We’ve g

ot a place in Biddenbrooke. Oh dear, he will be wondering where on earth I’ve got to. I said I’d call when I got in.’

I’m not sure what she means and I’m suddenly frightened she’s going to ask me to ring her husband. Where’s the ambulance? Where are the police? How long does it take, for God’s sake? ‘Are you cold?’ I ask, shoving my hands into my jacket pockets. ‘I wish I could do more to help make you comfortable. But I don’t think I should try to move you.’

‘No, let’s wait,’ she agrees, lightly, as if we’re at a bus stop, only mildly inconvenienced, as if it’s just one of those things. ‘I’m sure they’re on their way.’ And then she makes a sound that frightens me, a sort of sharp inhalation, a tiny gasp or cry, and then she stops talking, and when I say, ‘Alice? Alice?’ she doesn’t answer, but makes the noise again, and it’s such a small sort of noise, so hopeless somehow; and I know when I hear it that this is very serious after all.

I feel terribly alone then, and redundant: alone in the dark wood with the rain and the crying. And I look back over my shoulder, towards my car, the dazzle of its headlamps, and behind it I can see only darkness, and I keep looking and looking, and talking – though she’s no longer responding – and eventually I see lights, blue and white flashing lights, and I say, ‘Alice, they’re here, they’re coming, I can see them, it’s going to be fine, just hold on. They’re coming.’

I sit in the front seat of a police car and give a statement to someone called PC Wren. The windscreen is coursing with rain and the noise of it drumming relentlessly on the roof means she often has to ask me to repeat what I’ve just said. All the time I’m wondering what’s going on out there, with the arc lights and the heavy cutting gear and the hoists. I can’t see much through the misted-up window. Rubbing a patch clear with my cuff, I see a paramedic framed in the open door of the ambulance, looking at his watch and pouring something out of a Thermos. Some of his colleagues must be out there in the woods, I suppose. Maybe they tossed a coin for it, and he got lucky. No point us all catching pneumonia.

Wren closes her notebook. ‘That’s all for now,’ she says. ‘Thank you for your help. Someone will be in touch with you in the next day or so, just to tie up the loose ends.’

‘Is she going to be OK?’ I ask. I know it’s a stupid question, but it’s the only thing I can think of to say.

‘We’re doing our best. My colleagues will be able to update you in the next few days. You’re free to go now. Will you be all right to drive yourself to London? It might be sensible to go back to your parents’, spend the night there instead.’

‘I’ve got work tomorrow. I’ll be fine,’ I say. I reach for the door handle, but PC Wren puts a hand on my sleeve and squeezes it. ‘It’s hard,’ she says. There’s a real concern in her voice, and the unexpected kindness makes my eyes swim. ‘You did all that you could. Don’t forget that.’

‘I didn’t do anything. I couldn’t do anything. I hope she’s OK,’ I say. Then I open the door and step out. The rain and the wind come at me like a train. The woods, which had been so quiet, are now roaring: machinery pitched against the ferocity of a sudden winter storm. Caught in a huge artificial glow, a group of people are huddled close together, their fluorescent jackets shining with water, forming a screen around the car.

I run along the road, back to the Fiat, and get in, and in the abrupt silence of the interior I listen to my breathing. Then I start the engine and drive off. The wood falls away behind the car, like something letting go, and then there’s not much to see: the flash of catseyes and chevrons and triangles, the gradual build-up of the suburbs strung between darkened retail parks and roundabouts.

At home in the flat, once I’ve taken off my wet clothes and had a warm shower, I don’t quite know what to do with myself. It’s late, nearly eleven, and I don’t feel tired, and I don’t feel hungry, but I make some toast anyway, and a cup of tea, and grab the blanket from my bed and wrap myself in it. Then I sit in front of the television for a while, thinking about Alice, the voice in the dark; and, more distantly, about her husband. He’ll know by now. Perhaps he’ll be with her, in the hospital. Their lives thrown around like a handful of jacks, coming to settle in a new, dangerous configuration, all because of an icy patch on the road and a half-glimpse of a fox. The thought of this, the random luck and lucklessness of an ordinary life, frightens me as much as anything has tonight.

For once, I’m glad to be in the office. I get in early and sit at my desk, sipping the cappuccino I picked up at the sandwich bar on the corner. The cups are smaller than the ones you get at Starbucks but the coffee is stronger, and today, after a bad night’s sleep, that’s what I need. I look at my emails and check the queue: a few people have filed copy over the weekend, but not as many as had promised they would.

You’d have thought working on the books pages of the Questioner would be a doddle, that the section would more or less run itself; but every week it falls to me to rescue some celebrity professor or literary wunderkind from hanging participles or apostrophe catastrophes. I’m a subeditor, an invisible production drone: always out in the slips, waiting to save people from their own mistakes. If I fumble the catch I’ll hear about it from Mary Pym, the literary editor. Mary is at her best on the phone, buttering up her famous contacts, or at J. Sheekey, where she takes her pet contributors as compensation for the disappointing nature of the Questioner’s word rate.

One day, it is assumed, Mary’s expenses (the cabs, the first-class train tickets, the boutique hotels she checks into during the literary festival season) will have to be curtailed, as those of the other section heads have been. But for now, she sails on regardless. Stars still want to write for Mary, despite our dwindling circulation and the mounting sense that it’s all happening elsewhere, on the net.

No sign of Mary yet, but Tom from Travel is in, and we exchange hellos. Monday is a quiet day at the office: the newsroom on the west side of the building remains peaceful and empty until well into Tuesday. At the point when my weekend begins, when I’ve sent the books pages to press on Thursday afternoon, the newsroom is just starting to come to life, limbering up for the final sweaty sprint to deadline in the early hours of Sunday morning. Once or twice I’ve done a Saturday shift on the newsdesk, and it’s not to my taste: the swearing and antler-locking, the stories that fall through at the last minute, the eleventh-hour calls from ministers attempting to reshape a page lead. I always associate deadlines with the sour smell of vinegar-soused chips eaten out of polystyrene shells, a smell that is circulated endlessly by the air conditioning so that it’s still just perceptible this morning.

Mary arrives, her coat over one arm, her enormous handbag open to show off the gigantic turquoise Smythson diary in which she keeps all her secrets. She’s on her mobile, unctuously attending to someone’s ego. ‘I’ll get it biked round immediately,’ she says. ‘Unless you’d rather I had it couriered out?’ She cocks her head to one side, manhandles the diary on to my desk, and makes a note in her exquisite copperplate. ‘Absolutely!’ she says, nodding and writing. ‘So thrilled you can do this. There is the worry that he’s going off the boil rather. I’m sure you can make sense of it for us.’

She ends the call and moves on to her desk without acknowledging me. ‘Ambrose Pritchett is doing the new Paul Crewe,’ she murmurs a few moments later, not looking around, as her terminal bongs into life. ‘Filing a week on Thursday. Can you get the book to him before he leaves for the airport at ten forty-five? He wants to start it on the flight.’

I look at the clock. It’s nearly ten already. I don’t know where the preview copy is, and I know I can’t ask Mary. That sort of thing drives her up the wall. (‘Do I look like a fucking librarian, darling?’) So I ring the courier desk and book an urgent bike, and then I start to search through the shelves where we store advance copies. I try to file books by genre and alphabetically, but as neither Mary nor her twenty-three-year-old deputy Oliver Culpeper (every bit as bumptious as he is well connected) can be bothe

red with that approach, it’s not exactly a foolproof system. Eventually I find it, nudged behind Helen Simpson and the confessions of a coke-head stand-up with whom Mary shared a platform at Hay last summer. By the time I’ve written a covering note and shoved the Crewe in a padded envelope and taken it down to the couriers’ office, it’s quarter past. I’m standing in the elevator lobby, looking at my reflection in the stainless steel doors, when my mobile rings. I don’t recognise the number.

‘Frances Thorpe?’

‘Speaking,’ I say. Somehow I know it’s the police. It all comes back, the feeling of last night: the dark, the rain, the uselessness. I swallow hard. My throat is dry. In the doors, I see a pinched, nervous-looking girl, with blue shadows under her eyes: a pale, insignificant sort of person.

‘I’m Sergeant O’Driscoll from Brewster Street police station. My colleagues in Fulbury Norton have passed on your details. It’s with regard to the road traffic accident last night.’

‘Oh,’ I say, as the lift doors open. Road traffic accident. Why do they say that? What other sort of accident could there be on a road? ‘I’ve been thinking about her. Alice, I mean. Is there any news? How is she doing?’

‘We were hoping you could come down to the station, so we could go through your statement with you,’ he says. ‘Just to make sure you’re happy with it. Just in case anything else has occurred to you in the meantime.’

‘Well, yes, I could do that. I don’t have anything more to say. I’ve told you everything. But if it’ll help … How is she?’ I say again.

There’s a little pause. ‘I’m sorry to have to tell you this, Miss Thorpe, but she was very badly injured in the incident. She died at the scene.’

‘Oh,’ I say. Then, ‘How awful.’

The lift doors part on the fifth floor and I go back to my desk and write down the details on a Post-it.

At lunchtime, I leave the office, wrapping my red and purple scarf tightly around my throat and pulling it up over my mouth against the slicing cold, and start to walk, skirting the mainline station with its multiple retail opportunities, passing the old gasworks and the new library, cutting down several Georgian terraces and crossing the canal with its motionless skin of litter. Every so often, I walk by a café or a cheap restaurant with steamed-up windows, and the sound of coffee machines and cutlery comes out as someone arrives or leaves, and then the door swings shut and the sound dies away.

Alys, Always

Alys, Always